WHAT ARE INVERTERS?

An inverter is one of the most important pieces of equipment in a solar energy system. It’s a device that converts direct current (DC) electricity, which is what a solar panel generates, to alternating current (AC) electricity, which the electrical grid uses. In DC, electricity is maintained at constant voltage in one direction. In AC, electricity flows in both directions in the circuit as the voltage changes from positive to negative. Inverters are just one example of a class of devices called power electronics that regulate the flow of electrical power.

Fundamentally, an inverter accomplishes the DC-to-AC conversion by switching the direction of a DC input back and forth very rapidly. As a result, a DC input becomes an AC output. In addition, filters and other electronics can be used to produce a voltage that varies as a clean, repeating sine wave that can be injected into the power grid. The sine wave is a shape or pattern the voltage makes over time, and it’s the pattern of power that the grid can use without damaging electrical equipment, which is built to operate at certain frequencies and voltages.

The first inverters were created in the 19th century and were mechanical. A spinning motor, for example, would be used to continually change whether the DC source was connected forward or backward. Today we make electrical switches out of transistors, solid-state devices with no moving parts. Transistors are made of semiconductor materials like silicon or gallium arsenide. They control the flow of electricity in response to outside electrical signals.

A 1909 500-kilowatt Westinghouse “rotary converter,” an early type of inverter. Illustration courtesy of Wikimedia.

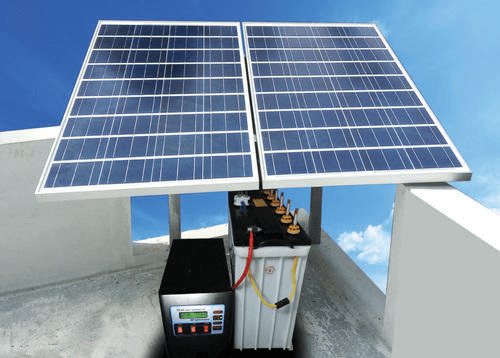

If you have a household solar system, your inverter probably performs several functions. In addition to converting your solar energy into AC power, it can monitor the system and provide a portal for communication with computer networks. Solar-plus–battery storage systems rely on advanced inverters to operate without any support from the grid in case of outages, if they are designed to do so.

TOWARD AN INVERTER-BASED GRID

Historically, electrical power has been predominantly generated by burning a fuel and creating steam, which then spins a turbine generator, which creates electricity. The motion of these generators produces AC power as the device rotates, which also sets the frequency, or the number of times the sine wave repeats. Power frequency is an important indicator for monitoring the health of the electrical grid. For instance, if there is too much load—too many devices consuming energy—then energy is removed from the grid faster than it can be supplied. As a result, the turbines will slow down and the AC frequency will decrease. Because the turbines are massive spinning objects, they resist changes in the frequency just as all objects resist changes in their motion, a property known as inertia.

As more solar systems are added to the grid, more inverters are being connected to the grid than ever before. Inverter-based generation can produce energy at any frequency and does not have the same inertial properties as steam-based generation, because there is no turbine involved. As a result, transitioning to an electrical grid with more inverters requires building smarter inverters that can respond to changes in frequency and other disruptions that occur during grid operations, and help stabilize the grid against those disruptions.

GRID SERVICES AND INVERTERS

Grid operators manage electricity supply and demand on the electric system by providing a range of grid services. Grid services are activities grid operators perform to maintain system-wide balance and manage electricity transmission better.

When the grid stops behaving as expected, like when there are deviations in voltage or frequency, smart inverters can respond in various ways. In general, the standard for small inverters, such as those attached to a household solar system, is to remain on during or “ride through” small disruptions in voltage or frequency, and if the disruption lasts for a long time or is larger than normal, they will disconnect themselves from the grid and shut down. Frequency response is especially important because a drop in frequency is associated with generation being knocked offline unexpectedly. In response to a change in frequency, inverters are configured to change their power output to restore the standard frequency. Inverter-based resources might also respond to signals from an operator to change their power output as other supply and demand on the electrical system fluctuates, a grid service known as automatic generation control. In order to provide grid services, inverters need to have sources of power that they can control. This could be either generation, such as a solar panel that is currently producing electricity, or storage, like a battery system that can be used to provide power that was previously stored.

Another grid service that some advanced inverters can supply is grid-forming. Grid-forming inverters can start up a grid if it goes down—a process known as black start. Traditional “grid-following” inverters require an outside signal from the electrical grid to determine when the switching will occur in order to produce a sine wave that can be injected into the power grid. In these systems, the power from the grid provides a signal that the inverter tries to match. More advanced grid-forming inverters can generate the signal themselves. For instance, a network of small solar panels might designate one of its inverters to operate in grid-forming mode while the rest follow its lead, like dance partners, forming a stable grid without any turbine-based generation.

Reactive power is one of the most important grid services inverters can provide. On the grid, voltage— the force that pushes electric charge—is always switching back and forth, and so is the current—the movement of the electric charge. Electrical power is maximized when voltage and current are synchronized. However, there may be times when the voltage and current have delays between their two alternating patterns like when a motor is running. If they are out of sync, some of the power flowing through the circuit cannot be absorbed by connected devices, resulting in a loss of efficiency. More total power will be needed to create the same amount of “real” power—the power the loads can absorb. To counteract this, utilities supply reactive power, which brings the voltage and current back in sync and makes the electricity easier to consume. This reactive power is not used itself, but rather makes other power useful. Modern inverters can both provide and absorb reactive power to help grids balance this important resource. In addition, because reactive power is difficult to transport long distances, distributed energy resources like rooftop solar are especially useful sources of reactive power.

TYPES OF INVERTERS

There are several types of inverters that might be installed as part of a solar system. In a large-scale utility plant or mid-scale community solar project, every solar panel might be attached to a single central inverter. String inverters connect a set of panels—a string—to one inverter. That inverter converts the power produced by the entire string to AC. Although cost-effective, this setup results in reduced power production on the string if any individual panel experiences issues, such as shading. Microinverters are smaller inverters placed on every panel. With a microinverter, shading or damage to one panel will not affect the power that can be drawn from the others, but microinverters can be more expensive. Both types of inverters might be assisted by a system that controls how the solar system interacts with attached battery storage. Solar can charge the battery directly over DC or after a conversion to AC.